Osteoporosis is very rare in the young. Diagnosis in children is usually based on history of fractures, in addition to bone mineral density evaluations. It is hard to definitively establish the prevalence: 6-19% of children are identified with poor skeletal health (the 6% number comes from quantitative computed tomography studies, 19% comes from dual emission x-ray absorptiometry. Specialists in osteoporosis hope that differential DXA scores for children and adults for osteoporosis diagnosing can be developed. A recent examination of this issue found that X-rays are not good enough for diagnosing osteoporosis in children and DEXA scans should be employed instead.

Juvenile idiopathic osteoporosis could be genetic, but it is usually secondary to inflammatory diseases that affect bone metabolism because of high cytokine levels and corticosteroid use. Juvenile osteoporosis can also be secondary to endocrine disorders such as hyperparathyroidism, hypercortisolism, Type 1 diabetes, hyperthyroidism, and hypogonadism which change the body's hormone levels. Secondary osteoporosis is a risk in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Children and teens with restricted mobility often develop lower bone density due to atrophy. You see this a lot in kids confined to wheelchairs or beds. Osteoporosis is also associated with neoplastic disorders and drugs such as glucocorticoids and anticonvulsants. It has been found that an unbalanced muscle-bone relationship is characteristic of juvenile osteoporosis. Nutritional problems such as vitamin D deficiency and intestinal malabsorption are also risk factors for children, the same as they are for adults.

The exact pathogenesis of juvenile osteoporosis is not known. It can develop any time up to age 13. The disease shows no sex predilection (Smith, 1995).

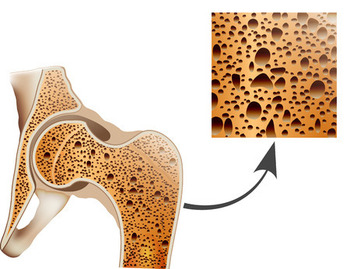

Osteoporosis happens when body loses boney tissue too fast or doesn't build it up fast enough. Normally in children and young adults, these are in balance. But in osteoporosis, they are out of balance and you experience a net loss. The opposite of osteoporosis is osteopetrosis when bones get too dense. Because children are growing, they normally experiece and increase in bone mass over the years. If a kid doesn't gain more bone as he or she grows up, juvenile osteoporosis can occur.

In majority of cases, juvenile osteoporosis naturally remits during or after puberty (Dent and Friedman, 1965; Cloutier et al., 1967; Kulkarni and Keshavamurthy, 2004). Nevertheless doctors tell affected children to restrict physical activity to avoid developing permanent deformities of the spine. Drugs like calcitriol (Vitamin D), biphosphonates, fluorides and calcitonin have been used with equivocal results (Krassas, 2000): in one study 3 out of 4 affected children treated with calcitriol showed significant improvement in bone mineralization after 12 months (Saggese et al., 1991), while another study did not show any effect of calcitriol on the disease (Jackson et al., 1988).

The consensus of the medical establishment is that the evidence is insufficient to advocate any treatment other than activity restriction until the osteoporosis subsides because of growth and density.

Some babies are born with osteopenia - low bone density. This happens more often in premature deliveries, where the fetus did not have time to develop bones of normal strength in a full third trimester. When the mother has a deficiency of Vitamin D or has been taking steroids or diuretics, the risk is also increased for infant osteopenia. Ultrasound and blood tests on the baby can help diagnose the condition. Neonatal specialists often recommend calcium and phosphorus supplements – these are more likely to work for newborns than for adults. Vitamin D supplements are also useful, especially for breastfed babies.